- Home

- J. R. R. Tolkien

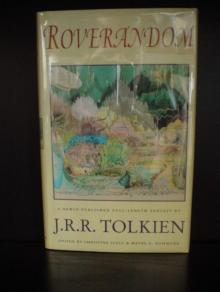

Roverandom

Roverandom Read online

Chapter One

Once upon a time there was a little dog, and his name was Rover. He was very small, and very young, or he would have known better; and he was very happy playing in the garden in the sunshine with a yellow ball, or he would never have done what he did.

Not every old man with ragged trousers is a bad old man: some are bone-and-bottle men, and have little dogs of their own; and some are gardeners; and a few, a very few, are wizards prowling round on a holiday looking for something to do. This one was a wizard, the one that now walked into the story. He came wandering up the garden-path in a ragged old coat, with an old pipe in his mouth, and an old green hat on his head. If Rover had not been so busy barking at the ball, he might have noticed the blue feather stuck in the back of the green hat, and then he would have suspected that the man was a wizard, as any other sensible little dog would; but he never saw the feather at all.

When the old man stooped down and picked up the ball - he was thinking of turning it into an orange, or even a bone or a piece of meat for Rover - Rover growled, and said:

'Put it down! ' Without ever a 'please'.

Of course the wizard, being a wizard, understood perfectly, and he answered back again:

'Be quiet, silly!' Without ever a 'please'.

Then he put the ball in his pocket, just to tease the dog, and turned away. I am sorry to say that Rover immediately bit his trousers, and tore out quite a piece. Perhaps he also tore out a piece of the wizard. Anyway the old man suddenly turned round very angry and shouted:

'Idiot! Go and be a toy!'

After that the most peculiar things began to happen. Rover was only a little dog to begin with, but he suddenly felt very much smaller. The grass seemed to grow monstrously tall and wave far above his head; and a long way away through the grass, like the sun rising through the trees of a forest, he could see the huge yellow ball, where the wizard had thrown it down again. He heard the gate click as the old man went out, but he could not see him. He tried to bark, but only a little tiny noise came out, too small for ordinary people to hear; and I don't suppose even a dog would have noticed it.

So small had he become that I am sure, if a cat had come along just then, she would have thought Rover was a mouse, and would have eaten him. Tinker would. Tinker was the large black cat that lived in the same house.

At the very thought of Tinker, Rover began to feel thoroughly frightened; but cats were soon put right out of his mind. The garden about him suddenly vanished, and Rover felt himself whisked off, he didn't know where. When the rush was over, he found he was in the dark, lying against a lot of hard things; and there he lay, in a stuffy box by the feel of it, very uncomfortably for a long while. He had nothing to eat or drink; but worst of all, he found he could not move. At first he thought this was because he was packed so tight, but afterwards he discovered that in the daytime he could only move very little, and with a great effort, and then only when no one was looking. Only after midnight could he walk and wag his tail, and a bit stiffly at that. He had become a toy. And because he had not said 'please' to the wizard, now all day long he had to sit up and beg. He was fixed like that.

After what seemed a very long, dark time he tried once more to bark loud enough to make people hear. Then he tried to bite the other things in the box with him, stupid little toy animals, really only made of wood or lead, not enchanted real dogs like Rover. But it was no good; he could not bark or bite.

Suddenly someone came and took off the lid of the box, and let in the light.

'We had better put a few of these animals in the window this morning, Harry,' said a voice, and a hand came into the box. 'Where did this one come from?' said the voice, as the hand took hold of Rover. 'I don't remember seeing this one before. It's no business in the threepenny box, I'm sure. Did you ever see anything so real-looking? Look at its fur and its eyes! '

'Mark him sixpence,' said Harry, 'and put him in the front of the window! '

There in the front of the window in the hot sun poor little Rover had to sit all the morning, and all the afternoon, till nearly tea-time; and all the while he had to sit up and pretend to beg, though really in his inside he was very angry indeed.

'I'll run away from the very first people that buy me,' he said to the other toys. 'I'm real. I'm not a toy, and I won't be a toy! But I wish someone would come and buy me quick. I hate this shop, and I can't move all stuck up in the window like this. '

'What do you want to move for?' said the other toys. 'We don't. It's more comfortable standing still thinking of nothing. The more you rest, the longer you live. So just shut up! We can't sleep while you're talking, and there are hard times in rough nurseries in front of some of us. '

They would not say any more, so poor Rover had no one at all to talk to, and he was very miserable, and very sorry he had bitten the wizard's trousers.

I could not say whether it was the wizard or not who sent the mother to take the little dog away from the shop. Anyway, just when Rover was feeling his miserablest, into the shop she walked with a shopping-basket. She had seen Rover through the window, and thought what a nice little dog he would be for her boy. She had three boys, and one was particularly fond of little dogs, especially of little black and white dogs. So she bought Rover, and he was screwed up in paper and put in her basket among the things she had been buying for tea.

Rover soon managed to wriggle his head out of the paper. He smelt cake. But he found he could not get at it; and right down there among the paper bags he growled a little toy growl. Only the shrimps heard him, and they asked him what was the matter. He told them all about it, and expected them to be very sorry for him, but they only said:

'How would you like to be boiled? Have you ever been boiled? '

'No! I have never been boiled, as far as I remember,' said Rover, 'though I have sometimes been bathed, and that is not particularly nice. But I expect boiling isn't half as bad as being bewitched. '

'Then you have certainly never been boiled,' they answered. 'You know nothing about it. It's the very worst thing that could happen to anyone - we are still red with rage at the very idea. '

Rover did not like the shrimps, so he said: 'Never mind, they will soon eat you up, and I shall sit and watch them! '

After that the shrimps had no more to say to him, and he was left to lie and wonder what sort of people had bought him.

He soon found out. He was carried to a house, and the basket was set down on a table, and all the parcels were taken out. The shrimps were taken off to the larder, but Rover was given straight away to the little boy he had been bought for, who took him into the nursery and talked to him.

Rover would have liked the little boy, if he had not been too angry to listen to what he was saying to him. The little boy barked at him in the best dog-language he could manage (he was rather good at it), but Rover never tried to answer. All the time he was thinking he had said he would run away from the first people that bought him, and he was wondering how he could do it; and all the time he had to sit up and pretend to beg, while the little boy patted him and pushed him about, over the table and along the floor.

At last night came, and the little boy went to bed; and Rover was put on a chair by the bedside, still begging until it was quite dark. The blind was down; but outside the moon rose up out of the sea, and laid the silver path across the waters that is the way to places at the edge of the world and beyond, for those that can walk on it. The father and mother and the three little boys lived close by the sea in a white house that looked right out over the waves to nowhere.

When the little boys were asleep, Rover stretched his tired, stiff legs and gave a little bark that nobody heard except an old wicked spider up a corner. Then he jumped from the chair to the bed, an

d from the bed he tumbled off onto the carpet; and then he ran away out of the room and down the stairs and all over the house.

Although he was very pleased to be able to move again, and having once been real and properly alive he could jump and run a good deal better than most toys at night, he found it very difficult and dangerous getting about. He was now so small that going downstairs was almost like jumping off walls; and getting upstairs again was very tiring and awkward indeed. And it was all no use. He found all the doors shut and locked, of course; and there was not a crack or a hole by which he could creep out. So poor Rover could not run away that night, and morning found a very tired little dog sitting up and pretending to beg on the chair, just where he had been left.

The two older boys used to get up, when it was fine, and run along the sands before their breakfast. That morning when they woke and pulled up the blind, they saw the sun

The Fellowship of the Ring

The Fellowship of the Ring The Hobbit

The Hobbit The Two Towers

The Two Towers The Return of the King

The Return of the King Tales From the Perilous Realm

Tales From the Perilous Realm Leaf by Niggle

Leaf by Niggle The Silmarillon

The Silmarillon The Book of Lost Tales, Part Two

The Book of Lost Tales, Part Two The Book of Lost Tales, Part One

The Book of Lost Tales, Part One The Book of Lost Tales 2

The Book of Lost Tales 2 Roverandom

Roverandom Smith of Wootton Major

Smith of Wootton Major The Fall of Arthur

The Fall of Arthur The Nature of Middle-earth

The Nature of Middle-earth The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring, The Two Towers, The Return of the King

The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring, The Two Towers, The Return of the King The Lay of Aotrou and Itroun

The Lay of Aotrou and Itroun lord_rings.qxd

lord_rings.qxd The Fall of Gondolin

The Fall of Gondolin The Book of Lost Tales, Part 1

The Book of Lost Tales, Part 1 The Book of Lost Tales, Part 2

The Book of Lost Tales, Part 2 The Lord of the Rings

The Lord of the Rings Tree and Leaf

Tree and Leaf The Children of Húrin

The Children of Húrin The Story of Kullervo

The Story of Kullervo Letters From Father Christmas

Letters From Father Christmas The History of Middle Earth: Volume 8 - The War of the Ring

The History of Middle Earth: Volume 8 - The War of the Ring Mr. Bliss

Mr. Bliss Unfinished Tales

Unfinished Tales The Adventures of Tom Bombadil

The Adventures of Tom Bombadil Beowulf: A Translation and Commentary, together with Sellic Spell

Beowulf: A Translation and Commentary, together with Sellic Spell The Silmarillion

The Silmarillion Beren and Lúthien

Beren and Lúthien