- Home

- J. R. R. Tolkien

The Story of Kullervo Page 11

The Story of Kullervo Read online

Page 11

The real scenery of the poems, the place of most of the action is Suomi, the Marshland – Finland as we call it – which the Finns themselves often name the Land of Ten Thousand Lakes. Short of going there, I imagine one could scarcely be made to see the land more vividly than by reading the Kalevala – the land of a century ago or more, at any rate, if not a land ravaged by modern progress. The poems are instinct with the love of it, of its bogs and wide marshes in which stand islands as it were formed by rising ground and sometimes topped with trees. The bogs are always with you – and a worsted or outwitted hero is invariably thrown into one. One sees the lakes and reed-fenced flats with slow rivers; the perpetual fishing; the pile-built houses – and then in winter the land covered with sleighs, and men faring over quick and firm alike on snow-shoes. Juniper, Pine, fir, aspen, birch are continually mentioned, rarely the oak, very seldom any other tree; and whatever they be nowadays in Finland the bear and wolf are in the Kalevala persons of great importance, and many sub-arctic animals figure in it too, that we do not know in England. The customs are all strange and so are the colours of everyday life; the pleasures and the dangers are

[The typescript stops here in mid-phrase on the last line of the page. The final two words, ‘dangers are’ are jammed in just beneath and partially overlapping the line above them, as if the paper had unexpectedly run out before the writer stopped typing. A hand-written comment in ink below the text notes: ‘[Text breaks off here].’ What would have been the following page apparently never was typed, but we may conjecture that had it been, it would have conformed more or less to the final page and three quarters of the manuscript draft.]

Notes and Commentary

99sudden collapse of the proper speaker. That Tolkien was filling in for two collapsed speakers some five to ten years apart, while not impossible, seems to stretch credibility. But since there is no evidence that this version of the talk was ever given, the opening sentence may simply have been transcribed without editing from the earlier version.

literature so very unlike. Note that the word is now spelled with one t.

103taken the position. A military expression, referring to capture of an enemy redoubt, not the assumption of a political or philosophical stance in argument.

104weird tales. This was the title of an American magazine of pulp fantasy fiction, first published in 1923, but not widely circulated in England. Tolkien’s allusion (if such it is) is likelier to have been to E.T.A. Hoffmann’s collection of stories, Weird Tales, translated from the German by J.T. Bealby and published in England in 1884.

105I would that we had more of it left – something of the same sort that belonged to the English. This statement, misleadingly associated in Humphrey Carpenter’s biography with Tolkien’s undergraduate time at Oxford, does not appear in the manuscript draft of 1914–15, written while he was still a student and before he went to war. It thus comes out of a different context from the original talk with which Carpenter conflated it, and is all the more to be associated with Tolkien’s burgeoning idea of a ‘mythology for England’. The remark was Tolkien’s response to the myth-and-nationalism movement that spread through Western Europe and the British Isles in the 19th and early 20th centuries but had been brought to a halt by the 1914 war. Out of that pre-war movement came Wilhelm Grimm’s Kinder- und Hausmärchen, Jacob Grimm’s Deutsche Mythologie, Jeremiah Curtin’s Myths and Folklore of Ireland, Moe and Asbjørnsen’s Norske Folkeeventyr, Lady Guest’s translation of the Welsh Mabinogion, in addition to Elias Lönnrot’s Old Kalevala (1835) and expanded Kalevala (1849) and a host of other myth and folklore collections.

107a no longer understood tradition. The 19th- and early 20th-century view of Welsh myth as seen in the Mabinogion was of a once-coherent concept behind the stories that had been garbled and misunderstood over time, partly through the supervention of Christianity and partly through the limited acquaintance of Christian redactors with the original stories.

108the catalogue of the heroes of Arthur’s court in the story of Kilhwch and Olwen. The Arthurian Court List is a ‘run’ of some 260 names, some historical, some legendary, some alleged to be Arthur’s relatives, some obviously fanciful, such as Clust mab Clustfeinad, ‘Ear son of Hearer’ and Drem mab Dremhidydd, ‘Sight son of Seer’. The recitation would have been a tour de force for the bard, as well as an evocation of a host of other untold stories.

Yspaddaden Penkawr. Yspaddaden ‘Chief/Head Giant’, is the father of Olwen, Kilhwch’s intended bride, and the tasks he assigns are not meant to test the prospective lover but to kill him. The character contributed not a little to Thingol, father of Lúthien, who assigned Beren the task of bringing back a Silmaril from the Iron Crown of Morgoth in the expectation that Beren would die in the attempt.

109feeling for colour that Keltic tales show. The spelling-change from Celtic in the manuscript essay to Keltic in the typescript revision is noteworthy but absent of explanation. Both spellings are recognized in modern dictionaries, probably due to the word having come into English twice, once through French from Latin and again through German from Greek. The C-spelling comes from the Latin Celtae and entered English in the 1600s through French Celtes. The K-spelling comes from the original form Keltoi, the name given by Greeks to tribes along the Danube and Rhone rivers, and its use by 19th-century German philologists. It has been pointed out to me by Edmund Weiner, co-author with Peter Gilliver and Jeremy Marshall of The Ring of Words: Tolkien and the Oxford English Dictionary, that Tolkien ‘was very much in a

114(as Francis Thompson says) ‘none will again behold’. Francis Thompson (1859–1907) was an English Catholic poet, best known for ‘The Hound of Heaven’, which Tolkien admired. The lines quoted here are from the concluding paragraphs of ‘Paganism Old and New: The Attempted Revival of the Pagan spirit, with its Tremendous Power of a Past, Though a Dead Past’ published in Thompson’s collection A Renegade Poet. Christopher Tolkien comments in a note in The Book of Lost Tales, Part One, that Tolkien ‘acquired the Works of Francis Thompson in 1913 and 1914’ (Lost Tales I, 29).

‘nostalgie de la boue’. Literally, ‘yearning for the mud’. Metaphorically, the phrase describes the desire, exemplified by the Romantic attraction to the primitive, to ascribe higher spiritual values to people and cultures popularly considered lower than one’s own. The attitude was widespread in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, initiated by antiquarians, energized by the discoveries of archaeologists, and fueled by anthropological research into comparative mythology and philology, all of which encouraged the finding of value in the archaic and primitive for its own sake. The word folklore, with its condescending assumption that the ‘folk’ are other (and less educated) than the users of the term, illustrates the mind-set.

the voice of Ahti in the noises of the sea. See the note on ‘Ahti’ following the manuscript version.

121Finnish minstrel cracking up his own profession. Talking up his own profession, praising it. Tolkien is using crack (derived from Middle English crak, ‘loud conversation, bragging talk’) as a verb in the dialectal expression to crack up, meaning ‘to praise, eulogize (a person or a thing)’. OED definition 8.

Tolkien, Kalevala, and ‘The Story of Kullervo’

The Story of Kullervo was an essential step on Tolkien’s road from adaptation to invention that resulted in the ‘Silmarillion’. It was the forerunner to and inspiration for his tragic epic of Túrin Turambar, one of the three ‘Great Tales’ of the fictive mythology of Middle-earth. Without the story itself to fit into the sequence, we have had only the beginning (Kalevala) and the end (Túrin) of the process, but not the crucial middle portion.

Humphrey Carpenter’s declaration in J.R.R. Tolkien: a biography, that episodes in Tolkien’s tale of Túrin Turambar were ‘derived quite consciously from the story of Kullervo in the Kalevala’ (J.R.R. Tolkien: a biography,

p. 96), is correct, yet seems in conflict with his judgment in the same paragraph that the influence of Kalevala on the Túrin story was ‘only superficial’ (ibid., p. 96). In fact, this judgment, like Carpenter’s misplacement of Tolkien’s ‘something of the same sort’ comment (see note), is quite off the mark. Far from being a superficial influence on Túrin, Kullervo’s story in Kalevala had a profound effect and was the root and source of the story, though filtered through Tolkien’s own (at that time unknown) adaptation. Carpenter’s biography was published in the same year – 1977 – as Christopher Tolkien’s edition of The Silmarillion, which gave readers their first look at the saga of Túrin and enabled them to compare it with the Kullervo story in Kalevala.

One of the earliest scholars* to seize the opportunity for comparison was Randel Helms, whose 1981 Tolkien and the Silmarils suggested that the story in Kalevala ‘is a tale that begs to be transformed’. But without access to The Story of Kullervo, Helms could only see Tolkien ‘learning to outgrow an influence, transform a source’, from the ‘lustful and murderous’ Kullervo of Kalevala (Helms, p. 6) to the lovable but wayward and wrong-headed Túrin Turambar of his own legendarium. Interest in Kullervo as a source thus grew slowly, with the critical commentary of necessity overleaping the unpublished story to jump straight from Kalevala to The Silmarillion. The predictable result was that even so distinguished a Tolkien scholar as Tom Shippey could concede that ‘the basic outline of the tale (of Túrin) owes much to the “Story of Kullervo” in the Kalevala’ (The Road to Middle-earth, p. 297), note the likenesses in ruined family, fosterage, incest with a sister, the conversation with the sword, and stop there.

The pace picked up as the 20th century turned to the 21st. Charles Noad conceded that ‘insofar as Kullervo served as the germ for Túrin, this was in one sense the beginning of the legendarium, but only as a model for future work’ (Tolkien’s Legendarium, p. 35). Given the lack of additional evidence, that, perforce, was all that scholars could conclude. Richard West, in general agreement with Carpenter and Helms, observed that ‘the story of Túrin did not remain a retelling of the story of Kullervo’, adding that ‘if we had the earliest version we would undoubtedly see that Tolkien started out that way, as he said, but at some point he diverged to tell a new story in the old tradition’ (ibid., 238). In her much later article, ‘Identifying England’s Lönnrot’ (Tolkien Studies I, 2004, 69–84), Anne Petty compared Tolkien with Elias Lönnrot, the compiler of Kalevala, calling attention to the way in which both mythmakers drew on earlier sources in applying their own organization and textualization to the story elements, Lönnrot’s sources being actual rune-singers as well as earlier folklore collectors, and Tolkien’s limited (as far as she knew) to the invented bards, scribes, and translators within his fiction. What Helms and Shippey and West and Petty lacked access to was the extra-mythological, transitional story and transitional character that contributed substantially to the transformation.

The appearance in 1981 of The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien gave us more information but little clarification, for the letters sent mixed signals, or at least showed Tolkien’s mixed feelings about the relative importance of Kalevala to his own mythology. His disclaimer that, as ‘The Children of Húrin’, the Kullervo story was ‘entirely changed except in the tragic ending’ (Letters, p. 345) probably influenced Carpenter’s ‘only superficial’ comment. But while it is understandable that Tolkien would want to privilege his own invention and establish his story’s independence from its source, other more positive references to Kalevala in his letters give a different impression. The mythology ‘greatly affected’ him (144); the language was like ‘an amazing wine’ (214); ‘Finnish nearly ruined [his] Hon. Mods.’ (87); Kalevala ‘set the rocket off in story’ (214); it was ‘the original germ of the Silmarillion’ (87). There is no question that Túrin Turambar is a fully realized character in his own right, far richer and better developed than the Kullervo of Kalevala, and situated in an entirely different context. In that respect, it could truthfully be said that the story was ‘entirely changed’. But an essential step was omitted. The figure of Kullervo passed through a formative middle stage between the two. The Story of Kullervo is the missing link in the chain of transmission. It is the bridge by which Tolkien crossed from the Land of Heroes to Middle-earth. How he made that crossing, and what he took with him are the subjects of my discussion.

Tolkien first read Kalevala in the English translation of W.F. Kirby in 1911 when he was at King Edward’s School in Birmingham. Though the work itself made a powerful impression on him, Kirby’s translation got a mixed reaction. He referred to it as ‘Kirby’s poor translation’ (Letters, p. 214), yet observed that in some respects it was ‘funnier than the original’ (Letters, p. 87). Both opinions may have motivated him to borrow from the Exeter College library in November 1911 a copy of Eliot’s A Finnish Grammar, an effort to learn enough Finnish to read Kalevala in the original. Although both Carpenter (Bodleian Library MS Tolkien B 64/6, folio 1; Biography, p. 73) and Scull & Hammond (Chronology, p. 55; Guide, p. 440) date The Story of Kullervo to 1914, according to Tolkien’s own account it was some time in 1912 that he began the project. A 1955 letter to W.H. Auden dated his attempt to ‘reorganize some of the Kalevala, especially the tale of Kullervo the hapless, into a form of my own’ to ‘the Honour Mods period ... . Say 1912 to 1913’ (Letters, pp. 214–15).

Tolkien’s memory for dates is not always fully reliable. Witness his dating of The Lord of the Rings to ‘the years 1936 to 1949’ (The Lord of the Rings, Foreword to the Second edition, xv) when The Hobbit itself was not published until September of 1937, and The Lord of the Rings – begun as a sequel to and initially called ‘the new Hobbit’ – not launched until December of that year. And the letter to Auden citing 1912 to 1913 was written some forty-three years after the ‘period’ it referred to. Nevertheless, the two references to ‘Hon. Mods.’ (Honour Moderations – a set of written papers comprising the first of two examinations taken by a degree candidate) are explicit, and identify a specific phase and time in Tolkien’s education. He sat for his Honour Moderations at the end of February 1913 (Biography, p. 62). The Hon. Mods. ‘period’ would thus be the time leading up to that, at the latest January 1913 (during which time he was also re-wooing Edith and persuading her to marry him), and more probably also the later months of the preceding year, 1912. He was also at that time apparently in the early stages of inventing Qenya (Carl Hostetter, personal communication), and some of the story’s invented names, imitatively Finnish in shape and phonology, have also a noticeable resemblance to early Qenya vocabulary.

Such a convergence of extracurricular interests – teaching himself Finnish (albeit unsuccessfully), ‘reorganizing’ the tale of Kullervo, and inventing Qenya – would surely be enough to explain Tolkien’s confession in the above-cited letter to Auden that he ‘came very near having my exhibition [scholarship] taken off me if not being sent down’ (Letters, p. 214). Nevertheless, this first practical union of ‘lit. and lang.’ embodied the principle Tolkien was to spend the rest of his life upholding, his staunchly maintained belief that ‘Mythology is language and language is mythology’ (Tolkien On Fairy-Stories, p. 181), that the two are not opposing poles, but opposite sides of the same coin. This was a period in Tolkien’s life rich with discoveries that fuelled and fed each other. Much later he wrote to a reader of The Lord of the Rings, ‘It was just as the 1914 War burst on me that I made the discovery that “legends” depend on the language to which they belong; but a living language depends equally on the “legends” which it conveys by tradition’ (Letters, p. 231). In the event, he did pass his Hon. Mods., though with a Second, not the hoped-for First, consequently did not have his exhibition taken off, and thankfully was not sent down, though he was persuaded to change from Classics to English Language and Literature. And in the long run it was legends and language that triumphed, for Kalevala and Finnish generated Qenya and The Story of Kullervo, and Tolkien’s Kullervo led to his T

úrin, to the ‘Silmarillion’, and the ‘Silmarillion’ led by way of The Hobbit to The Lord of the Rings.

Humphrey Carpenter’s dating of the manuscript to 1914 is probably based on Tolkien’s statement in the 1914 letter to Edith that [he was] ‘trying to turn one of the stories [of Kalevala] – which is really a very great story and most tragic – into a short story somewhat on the lines of Morris’ romances with chunks of poetry in between’ (Letters, p. 7). But the activity of a creative spark is hard to pin down. When and where and how does the impulse to tell a story begin? With an ‘I can do that’ moment while reading someone else’s text? With a mental light-bulb in the middle of the night? A note on the back of an envelope? A sentence scribbled on a napkin? Tolkien recognized the quotidian nature of inspiration, writing years later (1956), ‘I think a lot of this kind of work goes on at other (to say lower, deeper, or higher introduces a false gradation) levels, when one is saying how-do-you-do, or even “sleeping”’ (Letters, p. 231). In the case of The Story of Kullervo (unlike the opening of The Hobbit, by Tolkien’s own account written on the back of an exam) we will probably never know precisely.

Taking some time perhaps late in 1912 as the earliest possible starting date, and Carpenter’s 1914 as the terminus ad quem, we can see The Story of Kullervo as the work of a beginning writer. Whatever Tolkien’s immediate intent for the story, and whatever its contribution to his later work, it is best understood in retrospect as a trial piece, that of someone learning his craft and consciously imitating existing material. As Carpenter points out, and as Tolkien was at pains to acknowledge, the style is heavily indebted to William Morris, especially The House of the Wulfings, itself a stylistic mixture in which narrative prose gives frequent way to ‘chunks’ of poetic speech. Like its model, Tolkien’s story is deliberately antiquated, filled with poetic inversions – verbs before nouns, and archaisms – hath for has, doth for does, ‘him thought’ instead of ‘he thought’, ‘entreated’ in place of ‘treated’; as well as increasingly lengthy interpolations of spoken verse by various characters. Much of this style carries over to the earliest stories of Tolkien’s own mythology, such as ‘The Cottage of Lost Play’ in The Book of Lost Tales, Part Two, and may well have been an influence on the rhythmic, chanted speech of Tom Bombadil.

The Fellowship of the Ring

The Fellowship of the Ring The Hobbit

The Hobbit The Two Towers

The Two Towers The Return of the King

The Return of the King Tales From the Perilous Realm

Tales From the Perilous Realm Leaf by Niggle

Leaf by Niggle The Silmarillon

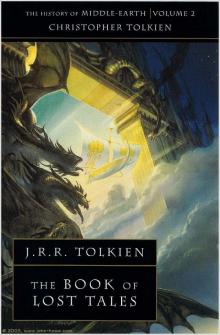

The Silmarillon The Book of Lost Tales, Part Two

The Book of Lost Tales, Part Two The Book of Lost Tales, Part One

The Book of Lost Tales, Part One The Book of Lost Tales 2

The Book of Lost Tales 2 Roverandom

Roverandom Smith of Wootton Major

Smith of Wootton Major The Fall of Arthur

The Fall of Arthur The Nature of Middle-earth

The Nature of Middle-earth The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring, The Two Towers, The Return of the King

The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring, The Two Towers, The Return of the King The Lay of Aotrou and Itroun

The Lay of Aotrou and Itroun lord_rings.qxd

lord_rings.qxd The Fall of Gondolin

The Fall of Gondolin The Book of Lost Tales, Part 1

The Book of Lost Tales, Part 1 The Book of Lost Tales, Part 2

The Book of Lost Tales, Part 2 The Lord of the Rings

The Lord of the Rings Tree and Leaf

Tree and Leaf The Children of Húrin

The Children of Húrin The Story of Kullervo

The Story of Kullervo Letters From Father Christmas

Letters From Father Christmas The History of Middle Earth: Volume 8 - The War of the Ring

The History of Middle Earth: Volume 8 - The War of the Ring Mr. Bliss

Mr. Bliss Unfinished Tales

Unfinished Tales The Adventures of Tom Bombadil

The Adventures of Tom Bombadil Beowulf: A Translation and Commentary, together with Sellic Spell

Beowulf: A Translation and Commentary, together with Sellic Spell The Silmarillion

The Silmarillion Beren and Lúthien

Beren and Lúthien