- Home

- J. R. R. Tolkien

The Lord of the Rings Page 14

The Lord of the Rings Read online

Page 14

‘Is it indeed?’ laughed Gildor. ‘Elves seldom give unguarded advice, for advice is a dangerous gift, even from the wise to the wise, and all courses may run ill. But what would you? You have not told me all concerning yourself; and how then shall I choose better than you? But if you demand advice, I will for friendship’s sake give it. I think you should now go at once, without delay; and if Gandalf does not come before you set out, then I also advise this: do not go alone. Take such friends as are trusty and willing. Now you should be grateful, for I do not give this counsel gladly. The Elves have their own labours and their own sorrows, and they are little concerned with the ways of hobbits, or of any other creatures upon earth. Our paths cross theirs seldom, by chance or purpose. In this meeting there may be more than chance; but the purpose is not clear to me, and I fear to say too much.’

‘I am deeply grateful,’ said Frodo; ‘but I wish you would tell me plainly what the Black Riders are. If I take your advice I may not see Gandalf for a long while, and I ought to know what is the danger that pursues me.’

‘Is it not enough to know that they are servants of the Enemy?’ answered Gildor. ‘Flee them! Speak no words to them! They are deadly. Ask no more of me! But my heart forbodes that, ere all is ended, you, Frodo son of Drogo, will know more of these fell things than Gildor Inglorion. May Elbereth protect you!’

‘But where shall I find courage?’ asked Frodo. ‘That is what I chiefly need.’

‘Courage is found in unlikely places,’ said Gildor. ‘Be of good hope! Sleep now! In the morning we shall have gone; but we will send our messages through the lands. The Wandering Companies shall know of your journey, and those that have power for good shall be on the watch. I name you Elf-friend; and may the stars shine upon the end of your road! Seldom have we had such delight in strangers, and it is fair to hear words of the Ancient Speech from the lips of other wanderers in the world.’

Frodo felt sleep coming upon him, even as Gildor finished speaking. ‘I will sleep now,’ he said; and the Elf led him to a bower beside Pippin, and he threw himself upon a bed and fell at once into a dreamless slumber.

Chapter 4

A SHORT CUT TO MUSHROOMS

In the morning Frodo woke refreshed. He was lying in a bower made by a living tree with branches laced and drooping to the ground; his bed was of fern and grass, deep and soft and strangely fragrant. The sun was shining through the fluttering leaves, which were still green upon the tree. He jumped up and went out.

Sam was sitting on the grass near the edge of the wood. Pippin was standing studying the sky and weather. There was no sign of the Elves.

‘They have left us fruit and drink, and bread,’ said Pippin. ‘Come and have your breakfast. The bread tastes almost as good as it did last night. I did not want to leave you any, but Sam insisted.’

Frodo sat down beside Sam and began to eat. ‘What is the plan for today?’ asked Pippin.

‘To walk to Bucklebury as quickly as possible,’ answered Frodo, and gave his attention to the food.

‘Do you think we shall see anything of those Riders?’ asked Pippin cheerfully. Under the morning sun the prospect of seeing a whole troop of them did not seem very alarming to him.

‘Yes, probably,’ said Frodo, not liking the reminder. ‘But I hope to get across the river without their seeing us.’

‘Did you find out anything about them from Gildor?’

‘Not much – only hints and riddles,’ said Frodo evasively.

‘Did you ask about the sniffing?’

‘We didn’t discuss it,’ said Frodo with his mouth full.

‘You should have. I am sure it is very important.’

‘In that case I am sure Gildor would have refused to explain it,’ said Frodo sharply. ‘And now leave me in peace for a bit! I don’t want to answer a string of questions while I am eating. I want to think!’

‘Good heavens!’ said Pippin. ‘At breakfast?’ He walked away towards the edge of the green.

From Frodo’s mind the bright morning – treacherously bright, he thought – had not banished the fear of pursuit; and he pondered the words of Gildor. The merry voice of Pippin came to him. He was running on the green turf and singing.

‘No! I could not!’ he said to himself. ‘It is one thing to take my young friends walking over the Shire with me, until we are hungry and weary, and food and bed are sweet. To take them into exile, where hunger and weariness may have no cure, is quite another – even if they are willing to come. The inheritance is mine alone. I don’t think I ought even to take Sam.’ He looked at Sam Gamgee, and discovered that Sam was watching him.

‘Well, Sam!’ he said. ‘What about it? I am leaving the Shire as soon as ever I can – in fact I have made up my mind now not even to wait a day at Crickhollow, if it can be helped.’

‘Very good, sir!’

‘You still mean to come with me?’

‘I do.’

‘It is going to be very dangerous, Sam. It is already dangerous. Most likely neither of us will come back.’

‘If you don’t come back, sir, then I shan’t, that’s certain,’ said Sam. ‘Don’t you leave him! they said to me. Leave him! I said. I never mean to. I am going with him, if he climbs to the Moon; and if any of those Black Riders try to stop him, they’ll have Sam Gamgee to reckon with, I said. They laughed.’

‘Who are they, and what are you talking about?’

‘The Elves, sir. We had some talk last night; and they seemed to know you were going away, so I didn’t see the use of denying it. Wonderful folk, Elves, sir! Wonderful!’

‘They are,’ said Frodo. ‘Do you like them still, now you have had a closer view?’

‘They seem a bit above my likes and dislikes, so to speak,’ answered Sam slowly. ‘It don’t seem to matter what I think about them. They are quite different from what I expected – so old and young, and so gay and sad, as it were.’

Frodo looked at Sam rather startled, half expecting to see some outward sign of the odd change that seemed to have come over him. It did not sound like the voice of the old Sam Gamgee that he thought he knew. But it looked like the old Sam Gamgee sitting there, except that his face was unusually thoughtful.

‘Do you feel any need to leave the Shire now – now that your wish to see them has come true already?’ he asked.

‘Yes, sir. I don’t know how to say it, but after last night I feel different. I seem to see ahead, in a kind of way. I know we are going to take a very long road, into darkness; but I know I can’t turn back. It isn’t to see Elves now, nor dragons, nor mountains, that I want – I don’t rightly know what I want: but I have something to do before the end, and it lies ahead, not in the Shire. I must see it through, sir, if you understand me.’

‘I don’t altogether. But I understand that Gandalf chose me a good companion. I am content. We will go together.’

Frodo finished his breakfast in silence. Then standing up he looked over the land ahead, and called to Pippin.

‘All ready to start?’ he said as Pippin ran up. ‘We must be getting off at once. We slept late; and there are a good many miles to go.’

‘You slept late, you mean,’ said Pippin. ‘I was up long before; and we are only waiting for you to finish eating and thinking.’

‘I have finished both now. And I am going to make for Bucklebury Ferry as quickly as possible. I am not going out of the way, back to the road we left last night: I am going to cut straight across country from here.’

‘Then you are going to fly,’ said Pippin. ‘You won’t cut straight on foot anywhere in this country.’

‘We can cut straighter than the road anyway,’ answered Frodo. ‘The Ferry is east from Woodhall; but the hard road curves away to the left – you can see a bend of it away north over there. It goes round the north end of the Marish so as to strike the causeway from the Bridge above Stock. But that is miles out of the way. We could save a quarter of the distance if we made a line for the Ferry from where we stand.’

/>

‘Short cuts make long delays,’ argued Pippin. ‘The country is rough round here, and there are bogs and all kinds of difficulties down in the Marish – I know the land in these parts. And if you are worrying about Black Riders, I can’t see that it is any worse meeting them on a road than in a wood or a field.’

‘It is less easy to find people in the woods and fields,’ answered Frodo. ‘And if you are supposed to be on the road, there is some chance that you will be looked for on the road and not off it.’

‘All right!’ said Pippin. ‘I will follow you into every bog and ditch. But it is hard! I had counted on passing the Golden Perch at Stock before sundown. The best beer in the Eastfarthing, or used to be: it is a long time since I tasted it.’

‘That settles it!’ said Frodo. ‘Short cuts make delays, but inns make longer ones. At all costs we must keep you away from the Golden Perch. We want to get to Bucklebury before dark. What do you say, Sam?’

‘I will go along with you, Mr. Frodo,’ said Sam (in spite of private misgivings and a deep regret for the best beer in the Eastfarthing).

‘Then if we are going to toil through bog and briar, let’s go now!’ said Pippin.

It was already nearly as hot as it had been the day before; but clouds were beginning to come up from the West. It looked likely to turn to rain. The hobbits scrambled down a steep green bank and plunged into the thick trees below. Their course had been chosen to leave Woodhall to their left, and to cut slanting through the woods that clustered along the eastern side of the hills, until they reached the flats beyond. Then they could make straight for the Ferry over country that was open, except for a few ditches and fences. Frodo reckoned they had eighteen miles to go in a straight line.

He soon found that the thicket was closer and more tangled than it had appeared. There were no paths in the undergrowth, and they did not get on very fast. When they had struggled to the bottom of the bank, they found a stream running down from the hills behind in a deeply dug bed with steep slippery sides overhung with brambles. Most inconveniently it cut across the line they had chosen. They could not jump over it, nor indeed get across it at all without getting wet, scratched, and muddy. They halted, wondering what to do. ‘First check!’ said Pippin, smiling grimly.

Sam Gamgee looked back. Through an opening in the trees he caught a glimpse of the top of the green bank from which they had climbed down.

‘Look!’ he said, clutching Frodo by the arm. They all looked, and on the edge high above them they saw against the sky a horse standing. Beside it stooped a black figure.

They at once gave up any idea of going back. Frodo led the way, and plunged quickly into the thick bushes beside the stream. ‘Whew!’ he said to Pippin. ‘We were both right! The short cut has gone crooked already; but we got under cover only just in time. You’ve got sharp ears, Sam: can you hear anything coming?’

They stood still, almost holding their breath as they listened; but there was no sound of pursuit. ‘I don’t fancy he would try bringing his horse down that bank,’ said Sam. ‘But I guess he knows we came down it. We had better be going on.’

Going on was not altogether easy. They had packs to carry, and the bushes and brambles were reluctant to let them through. They were cut off from the wind by the ridge behind, and the air was still and stuffy. When they forced their way at last into more open ground, they were hot and tired and very scratched, and they were also no longer certain of the direction in which they were going. The banks of the stream sank, as it reached the levels and became broader and shallower, wandering off towards the Marish and the River.

‘Why, this is the Stock-brook!’ said Pippin. ‘If we are going to try and get back on to our course, we must cross at once and bear right.’

They waded the stream, and hurried over a wide open space, rush-grown and treeless, on the further side. Beyond that they came again to a belt of trees: tall oaks, for the most part, with here and there an elm tree or an ash. The ground was fairly level, and there was little undergrowth; but the trees were too close for them to see far ahead. The leaves blew upwards in sudden gusts of wind, and spots of rain began to fall from the overcast sky. Then the wind died away and the rain came streaming down. They trudged along as fast as they could, over patches of grass, and through thick drifts of old leaves; and all about them the rain pattered and trickled. They did not talk, but kept glancing back, and from side to side.

After half an hour Pippin said: ‘I hope we have not turned too much towards the south, and are not walking longwise through this wood! It is not a very broad belt – I should have said no more than a mile at the widest – and we ought to have been through it by now.’

‘It is no good our starting to go in zig-zags,’ said Frodo. ‘That won’t mend matters. Let us keep on as we are going! I am not sure that I want to come out into the open yet.’

They went on for perhaps another couple of miles. Then the sun gleamed out of ragged clouds again and the rain lessened. It was now past mid-day, and they felt it was high time for lunch. They halted under an elm tree: its leaves though fast turning yellow were still thick, and the ground at its feet was fairly dry and sheltered. When they came to make their meal, they found that the Elves had filled their bottles with a clear drink, pale golden in colour: it had the scent of a honey made of many flowers, and was wonderfully refreshing. Very soon they were laughing, and snapping their fingers at rain, and at Black Riders. The last few miles, they felt, would soon be behind them.

Frodo propped his back against the tree-trunk, and closed his eyes. Sam and Pippin sat near, and they began to hum, and then to sing softly:

Ho! Ho! Ho! to the bottle I go

To heal my heart and drown my woe.

Rain may fall and wind may blow,

And many miles be still to go,

But under a tall tree I will lie,

And let the clouds go sailing by.

Ho! Ho! Ho! they began again louder. They stopped short suddenly. Frodo sprang to his feet. A long-drawn wail came down the wind, like the cry of some evil and lonely creature. It rose and fell, and ended on a high piercing note. Even as they sat and stood, as if suddenly frozen, it was answered by another cry, fainter and further off, but no less chilling to the blood. There was then a silence, broken only by the sound of the wind in the leaves.

‘And what do you think that was?’ Pippin asked at last, trying to speak lightly, but quavering a little. ‘If it was a bird, it was one that I never heard in the Shire before.’

‘It was not bird or beast,’ said Frodo. ‘It was a call, or a signal – there were words in that cry, though I could not catch them. But no hobbit has such a voice.’

No more was said about it. They were all thinking of the Riders, but no one spoke of them. They were now reluctant either to stay or go on; but sooner or later they had got to get across the open country to the Ferry, and it was best to go sooner and in daylight. In a few moments they had shouldered their packs again and were off.

Before long the wood came to a sudden end. Wide grass-lands stretched before them. They now saw that they had, in fact, turned too much to the south. Away over the flats they could glimpse the low hill of Bucklebury across the River, but it was now to their left. Creeping cautiously out from the edge of the trees, they set off across the open as quickly as they could.

At first they felt afraid, away from the shelter of the wood. Far back behind them stood the high place where they had breakfasted. Frodo half expected to see the small distant figure of a horseman on the ridge dark against the sky; but there was no sign of one. The sun escaping from the breaking clouds, as it sank towards the hills they had left, was now shining brightly again. Their fear left them, though they still felt uneasy. But the land became steadily more tame and well-ordered. Soon they came into well-tended fields and meadows: there were hedges and gates and dikes for drainage. Everything seemed quiet and peaceful, just an ordinary corner of the Shire. Their spirits rose with every step. The line of the Rive

r grew nearer; and the Black Riders began to seem like phantoms of the woods now left far behind.

They passed along the edge of a huge turnip-field, and came to a stout gate. Beyond it a rutted lane ran between low well-laid hedges towards a distant clump of trees. Pippin stopped.

‘I know these fields and this gate!’ he said. ‘This is Bamfurlong, old Farmer Maggot’s land. That’s his farm away there in the trees.’

‘One trouble after another!’ said Frodo, looking nearly as much alarmed as if Pippin had declared the lane was the slot leading to a dragon’s den. The others looked at him in surprise.

‘What’s wrong with old Maggot?’ asked Pippin. ‘He’s a good friend to all the Brandybucks. Of course he’s a terror to trespassers, and keeps ferocious dogs – but after all, folk down here are near the border and have to be more on their guard.’

‘I know,’ said Frodo. ‘But all the same,’ he added with a shamefaced laugh, ‘I am terrified of him and his dogs. I have avoided his farm for years and years. He caught me several times trespassing after mushrooms, when I was a youngster at Brandy Hall. On the last occasion he beat me, and then took me and showed me to his dogs. “See, lads,” he said, “next time this young varmint sets foot on my land, you can eat him. Now see him off!” They chased me all the way to the Ferry. I have never got over the fright – though I daresay the beasts knew their business and would not really have touched me.’

Pippin laughed. ‘Well, it’s time you made it up. Especially if you are coming back to live in Buckland. Old Maggot is really a stout fellow – if you leave his mushrooms alone. Let’s get into the lane and then we shan’t be trespassing. If we meet him, I’ll do the talking. He is a friend of Merry’s, and I used to come here with him a good deal at one time.’

They went along the lane, until they saw the thatched roofs of a large house and farm-buildings peeping out among the trees ahead. The Maggots, and the Puddifoots of Stock, and most of the inhabitants of the Marish, were house-dwellers; and this farm was stoutly built of brick and had a high wall all round it. There was a wide wooden gate opening out of the wall into the lane.

The Fellowship of the Ring

The Fellowship of the Ring The Hobbit

The Hobbit The Two Towers

The Two Towers The Return of the King

The Return of the King Tales From the Perilous Realm

Tales From the Perilous Realm Leaf by Niggle

Leaf by Niggle The Silmarillon

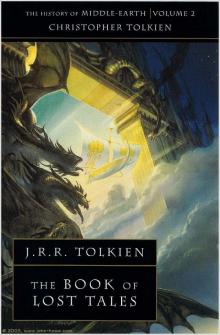

The Silmarillon The Book of Lost Tales, Part Two

The Book of Lost Tales, Part Two The Book of Lost Tales, Part One

The Book of Lost Tales, Part One The Book of Lost Tales 2

The Book of Lost Tales 2 Roverandom

Roverandom Smith of Wootton Major

Smith of Wootton Major The Fall of Arthur

The Fall of Arthur The Nature of Middle-earth

The Nature of Middle-earth The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring, The Two Towers, The Return of the King

The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring, The Two Towers, The Return of the King The Lay of Aotrou and Itroun

The Lay of Aotrou and Itroun lord_rings.qxd

lord_rings.qxd The Fall of Gondolin

The Fall of Gondolin The Book of Lost Tales, Part 1

The Book of Lost Tales, Part 1 The Book of Lost Tales, Part 2

The Book of Lost Tales, Part 2 The Lord of the Rings

The Lord of the Rings Tree and Leaf

Tree and Leaf The Children of Húrin

The Children of Húrin The Story of Kullervo

The Story of Kullervo Letters From Father Christmas

Letters From Father Christmas The History of Middle Earth: Volume 8 - The War of the Ring

The History of Middle Earth: Volume 8 - The War of the Ring Mr. Bliss

Mr. Bliss Unfinished Tales

Unfinished Tales The Adventures of Tom Bombadil

The Adventures of Tom Bombadil Beowulf: A Translation and Commentary, together with Sellic Spell

Beowulf: A Translation and Commentary, together with Sellic Spell The Silmarillion

The Silmarillion Beren and Lúthien

Beren and Lúthien