- Home

- J. R. R. Tolkien

The Nature of Middle-earth Page 9

The Nature of Middle-earth Read online

Page 9

The number of children produced by a married pair was again naturally affected by the characters (mental and physical) of the persons concerned. But also by various accidents of life; and by the “age” at which the marriage began, especially the age of the Elf-woman.

Even in the earliest generations after the Awaking, more than six children was very rare, and the average number soon (as the vigour of hröar and fëar began more and more to be applied to other “expenditures”) was reduced to four. Six children were never attained by those wedding after ages 48 for Elf-men and 36 for Elf-women. In the later Ages (Second and Third) two children were usual.

In the early generations the Quendi seem to have arranged their lives normally so as to have a continuous ‘Time of the Children’ (or Onnalúmë) until their desires were fulfilled and (as they said) the generation was complete. This was still often the case with married pairs later, if they lived in times of peace and could control their own lives; but it was not always done, and in the later Ages children might be born after long and irregular intervals.

This often depended upon the circumstances of the parents. For at all times the Quendi desired to dwell in company with husband or wife during the bearing of a child, and during its early youth. (For these years were one of chief joy to them, and longest and dearest held in memory.)[5] So that the Quendi did not wed, or if wedded did not engender children, in troublous times or perils (if these could be foreseen).

After a child-birth a “time of repose” was always taken, and this again tended to increase in length.[fn8] This time (being concerned mainly with bodily refreshment) was reckoned in growth-years or olmendi. It was seldom less than one olmen (or 12 löar); but it might be much more. And usually (but not necessarily) it was progressively increased after each birth of a continuous Onnalúmë, in such series as: löar 12/18/24/30/36 or often 12/24/36/48/60; or in the case of smaller families: 12/30/48/66. But these series are only averages, or formulated examples. In practice the intervals were more variable. They normally occupied some exact number of löar, since conception (and therefore birth 9 löar later) was nearly always in Spring; but they were not necessarily in exact twelves or sixes, nor in regular progression.

A completed “generation” or Onnalúmë of six children could thus in theory occupy at minimum 114 löar. That is 6 × 9 gestations + 5 × 12 intervals. This was naturally rare. At theoretic maximum it might occupy the whole time between maturity of the mother (18) to the end of her “youth” (90), or 72 yéni: i.e., 10,368 löar. But this never occurred. So great an interval (as this average of over 2,060 löar) never occurred, and in cases where large families were engendered the intervals were seldom greater than 1 coimen or ‘life-year’ (144 löar). Six coimendi was in fact the longest interval found in the early histories; except in Aman where “waning” was retarded, and an interval of 12 coimendi occasionally recorded.

In the early Ages (before the Great March) an Onnalúmë of several children (6, 5, 4) seems usually to have occupied about 1 coimen (equivalent to 1 Valian year or 144 löar) from first birth to last birth: that is, 144 + 9 löar from the beginning of the “generation” with the first conception to the last birth.

The Quendi never “fell” as a race – not in the sense in which they and Men themselves believed that the Second Children had “fallen”.[6] Being “tainted” with the Marring (which affected all the “flesh of Arda” from which their hröar were derived and were nourished),[7] and having also come under the Shadow of Melkor before their Finding and rescue, they could individually do wrong. But they never (not even the wrong-doers) rejected Eru, nor worshipped either Melkor or Sauron as a god – neither individually or as a whole people. Their lives, therefore, came under no general curse or diminishment; and their primeval and natural life-span, as a race, by “doom” co-extensive with the remainder of the Life of Arda, remained unchanged in all their varieties.

Of course the Quendi could be terrorized and daunted. In the remote past before the Finding, or in the Dark Years of the Avari after the departure of the Eldar, or in the histories of the Silmarillion, they could be deceived; and they could be captured and tormented and enslaved. Then under force and fear they might do the will of Melkor or Sauron, and even commit grave wrongs. But they did so as slaves who nonetheless in heart knew and never rejected the truth. (There is no record of any Elf ever doing more than carrying out Melkor’s orders under fear or compulsion. None ever called him Master, or Lord, or did any evil act uncommanded to obtain his favour.) Thus, though the carrying out of evil commands, quite apart from the sufferings of slavery and torment, clearly exhausted the “youth” and life-vigour of those unfortunate Elves who came under the power of the Shadow, this evil and diminishment was not heritable.

The lives of the Quendi, also, cannot be supposed to have been affected by living “under the Sun”, in Middle-earth. As now is known and recognized in the Histories, the Sun was part of the original structure of Arda, and not devised only after the Death of the Trees. The Quendi were, therefore, designed in nature to dwell in Middle-earth “under the Sun”.

The situation in Aman requires some consideration. It appears that in Aman the Quendi were little affected in their modes of growth (olmië) and life (coivië). How was that so? In Aman the Valar maintained all things in bliss and health, and corporeal living things (such as plants and beasts) appear to have “aged” or changed no quicker than Arda itself. A year to them was a Valian Year, but even its passage brought them no nearer to death – or not visibly and appreciably: not until the end of Arda itself would the withering appear. Or so it is said. But it seems that there was no general “law” of time governing all things in Aman. Each living thing, individually and not only each kind or variety of living things, was under the care of the Valar and their attendant Máyar.[8] Each was maintained in some form of beauty or use, for the Valar and for one another. This plant might be allowed to ripen to seed, and that plant be maintained in blossom.[9] This beast might walk in the strength and freedom of its youth, another might find a mate and bring up its young.[fn9]

Now it is possible (though not certain)[fn10] that the Valar could have graced or blessed the Eldar, singly or as a whole, in like manner. But they did not do so. For, though they had (wisely or not) transported them to Aman, to save them from Melkor, they knew that they should not “meddle with the Children”, or attempt to change their natures, or dominate them in any way, or wrest their being (in hröa or fëa) to any other mode than that in which Eru had designed them.

The only effect of residence in Aman upon the Eldar seems to have been this: in the bliss and health of Aman their bodies remained in vigour, and were able to support the great growth in knowledge and ardour of their spirits without any appreciable waning (except in very special cases: such as that of Míriel). Those who entered Aman, from without or by birth, would leave it in the same health and vigour as they had to begin with.

This slower rate of growth and of ageing natural to the Quendi, as compared with Men, has nothing to do with the perception or use of Time. This was primarily of the fëa, whereas growth and ageing were of the hröa. The Eldar say of themselves (and it may be in some degree true also of Men) that when “persons” – in whole being, fëa and hröa,[10] are fully occupied with things that are of deep concern to their true natures, and are therefore of great interest and delight to them, Time seems to pass quickly, and not the reverse. That is: the full and minutely divided employment of Time does not make it seem longer than the same period passed in less activity or in idleness, but shorter. It is not with Time as it might be with a road or path. If this were closely and minutely inspected it would take long to traverse, and would maybe seem to be itself of greater length; for that inspection could only be carried out by slowing the rate of normal travel. But the fëa may quicken its speed of thought and action, and achieve more, or attend more minutely to events, in one space of time than in another.

Thus the Quendi did not (and do not) live slowly

, moving ponderously like tortoises while Time flickers past them and their sluggish limbs and thoughts! Indeed, they move and think swifter than Men, and achieve more than any Man in any given length of time. But they have a far greater native vitality and energy to draw upon, so that it takes, and will take a very great length of years to expend it.

However, they were from the beginning, and so still remain, close kin of Men, the Second Children, and their actions, desires, and talents are akin, as are their modes of perception and thought. They do not think and act in ways unobservable or actually incomprehensible to Men. To a Man Elves appear to speak rapidly (but with clarity and precision) unless they a little retard their speech for Men’s sake; to move quickly and featly, unless in urgency, or much moved, or eager in their work, when the movement of their hands, for instance, become too swift for human eyes to follow closely. Only their perception, and their thought and reasoning, seems normally beyond human rivalry in speed.

The main text ends here, but on the following (and last) sheet Tolkien drew up two tables for numerical aid. I give the first here in full:

Some tables for reckoning approximate equivalents of Elvish “age” to human terms.

Olmendi ‘growth-years’: 1 olmen = 12 löar (sun-years)

12 olmendi = 1 Valian Year

= 1 coimen

= 1 yén

= 144 löar

Coimendi ‘life-years’ 1 coimen = 12 olmendi

= 144 löar

Gestation (colbamarië) ¾ olmen = 9 löar

Maturity (quantolië) achieved

for males in 24 olmendi = 288 löar

for females in 18 olmendi[fn11] = 216 löar

End of “youth” naturally is if not hastened (or more seldom retarded) achieved for both sexes in 72 coimendi from maturity = 10,368 löar

The “end of youth” thus came for an Elf-man after 74 coimendi = 10,656 löar; for an Elf-woman after 73½ coimendi – 10,584 löar.

The second table calculates the total number of löar for the coimendi from 1 to 80: being 144 to 11,520 in 144-year increments. To the end of this table Tolkien appended a note:

☞ An Elf ages from 22 to 24 “life-years” [i.e., 3,168 to 3,456 löar] in each Age of Arda.

XIII

KEY DATES

The texts presented here occupy 16 sides of nine sheets of mixed nature, clipped together by Tolkien, and written in a variety of hands and implements of greatly varying legibility. The characteristics of each are described for the individual texts below. As for a probable date for the bundle as a whole, this is provided by the reuse of two engagement calendar pages, for 8–14 Feb. and 1–7 Mar. 1959, for Text 3.

TEXT 1

This text occupies sides 1–4 and 15–16 (sheets 1–2 and 9, all unlined paper) of the clipped bundle, in which the other texts are interspersed between sheets 2 and 9. It is written in black nib-pen in what is a mostly clear hand, with some rougher alterations and re-arrangements made subsequently in green ball-point pen.

Of special note in this text is the introduction, or at least suggestion, of events and motives not previously found elsewhere, including: the sending of Melian and (at least three of) the later Istari to Cuiviénen for a time as guardians of the Elves; the doubt of the younger Elves at Cuiviénen as to the existence of the Valar, and the prideful sense among these Elves of a “mission” to themselves defeat Melkor and possess Arda; and of the refusal of the 144 First Elves, “the Seniors”, to depart on the Great March.

Suggestions for key dates

“Days of Bliss” begin VY 1.

First löa of VY 850 First Age 1. Quendi awake in the Spring (144 in number). Melian warned in a dream leaves Valinor and goes to Endor.

VY 854 576.[1] About the time the 12th generation of Quendi first appeared, Melkor (or his agents) first get wind of the Quendi.[2] Quendi originally warned by Eru or emissaries, and forbidden (or advised?) not yet to stray far. Adventurous Elves did so, nonetheless, and some were caught?

VY 858 1152.[3] Shadows of fear begin to dim the natural happiness of the Quendi. They hold debate, and it appears that already some hearts are overshadowed. Younger elves (who never personally heard the Voice of Eru) doubt the existence of the Valar (of whom they heard from Melian?). The do not waver in allegiance, but in pride believe that their mission is to fight the Dark, and ultimately to possess the world of Arda. This “heresy”, though driven under at the Finding, is the seed of the later Fëanorian trouble.

end of VY 864 2016. Oromë finds the Quendi. He dwells with them for 48 years (to 2064).

VY 865/2 2018. Tidings reach Valinor.

VY 865/44 2060. Melkor seeks to attack Oromë. Oromë informs Manwë. Tulkas is sent.

VY 865/48 2064. Leaving guards, Oromë returns to Valinor.

D[ays of] B[liss]

VY 865/50 2066. Oromë reports. Council of the Valar. They resolve on behalf of the Quendi to make War on Melkor, and begin to prepare for the great struggle. They debate what is to be done with the Quendi, since they fear Endor will suffer great damage. Most of the Valar think they should remove the Quendi to safety, at least temporarily. Ulmo in chief (also Yavanna?) is against this: It is not Eru’s intention that they should reside in such a place; and could not or would not be temporary. He prophesies that once brought thither the Quendi would either have to be sent back to their proper homes against their will; or would rebel and do so against the will of the Valar.

DB 865/56 2072. Birth of Ingwë of the House of Imin.[4]

DB 865/104 2120. Birth of Finwë.

DB 865/110 2126. Birth of Elwë.

VY 866/1 2163.[5] Oromë returns to Cuiviénen, with more mayar. (Melkor becomes suspicious, and guesses war is purposed against him, because of the Quendi. During Oromë’s absence his emissaries were busy, and many lies circulate. The “heresy” awakes in new form: the Valar clearly do exist; but they have abandoned Endor: rightly as the appointed realm of the Quendi. Now they are becoming jealous, and wish to control the Quendi as vassals, and so re-possess themselves of Endor. Finwë, a gallant and adventurous young quende, direct descendant of Tata (therefore 25th gen.), is much taken by these ideas; less so his friend Elwë, descendant of Enel.)

DB 866/13 2175. Oromë remains for 12 years, and then is summoned to return for the councils and war-preparations. Manwë has decided that the Quendi should come to Valinor, but on urgent advice of Varda, they are only to be invited, and are to be given free choice.[6] The Valar send five Guardians (great spirits of the Maiar) – with Melian (the only woman, but the chief) these make six. The others were Tarindor (later Saruman), Olórin (Gandalf), Hrávandil (Radagast), Palacendo, and Haimenar.[7] Tulkas goes back. Oromë remains in Cuiviénen for 3 more years: VY 866/13–16, FA 2175–8.

DB 866/14–24 2176–86. The Valar continue their war-preparation. (Melkor also. Angband is strengthened and Sauron put in command.)

DB 866/49 2211. The preparations and plans are now nearly complete. The Valar decide that the Quendi should now be “invited”. But Manwë decrees that first the Quendi should send representatives as ambassadors to Valinor (Ulmo insists this is perilously near to overaweing their free will.) Oromë is sent back to Cuiviénen.

DB 866/50 2212. Oromë sets out from Cuiviénen with the Three Ambassadors. These were elected by the Quendi, one from each of their kindreds. Only the youngest Elves are willing. Ingwë, Finwë, and Elwë are chosen. (Ingwë belonged to the 24th gen., and was then 140 years old; Finwë was of the 25th gen. and 92, Elwë of same and 86.)[8]

DB 866/51 2213. Ingwë, Finwë, and Elwë arrive in Valinor. They are indeed dazzled and overawed. Finwë (with “heretical” leanings) is most converted, and ardent for acceptance. (He has a lover, Míriel, who is devoted to crafts, and he longs for her to have the marvellous chance of learning new skills. Ingwë is already married, and more cool, but desires to dwell in the presence of Varda. Elwë would prefer the “lesser light, and shadows” of Endor, but will follow Finwë his friend.)

&nb

sp; DB 866/60 2222. They remain 9 years, for Ingwë and Finwë are reluctant to hurry away.

DB 866/61 2223. The “Ambassadors” return. Great Debate of the Quendi. A few refuse even to attend. Imin, Tata, and Enel are ill-pleased, and regard the affair as a revolt on the part of the youngest Quendi, to escape their authority. None of the First Elves (144) accept the invitation. Hence the Avari called and still call themselves “the Seniors”.

Imin makes a speech, claiming that the “Three Fathers” have authority (from Eru, since He woke them first), and should decide. Tata says that each of the Fathers should have authority but only over his own Company. Enel agrees to this, but makes it clear that he is against the move. Imin claims to be “Father of All Quendi”, but urges that they should at least in the end all do the same, and not break up the Kindred.

The Ambassadors speak. Ingwë speaks with great deference of the Three Fathers, and especially of Imin. He says it was a mistake that Imin, Tata, and Enel did not go themselves, for they could have exerted authority with judgement. But since they sent him and his companions as their representatives, they should now (in spite of their youth) pay great heed to their reports and opinions. He thinks they have no conception of the riches of beauty[9] in Valinor. He asks Oromë if it is still possible for Imin, Tata, and Enel to go to Valinor? Oromë says “yes, if they will go at once”. The Three Fathers are not willing.

Finwë speaks similarly, but lays stress on the riches of knowledge and crafts in Valinor. Also he says that the Quendi have only seen “the skirts of the Shadow”, and have no idea of its dreadful power, or of the power of the Valar – and do not realize what the War (which the Valar are about to wage on behalf of the Quendi) will entail to Endor. His speech is very effective, as large numbers of the Quendi who cannot conceive of Valinor’s attraction are nonetheless frightened of what may befall them if they remain.

The Fellowship of the Ring

The Fellowship of the Ring The Hobbit

The Hobbit The Two Towers

The Two Towers The Return of the King

The Return of the King Tales From the Perilous Realm

Tales From the Perilous Realm Leaf by Niggle

Leaf by Niggle The Silmarillon

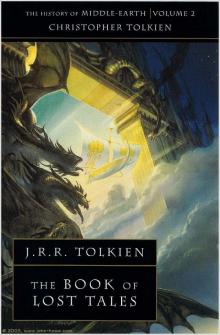

The Silmarillon The Book of Lost Tales, Part Two

The Book of Lost Tales, Part Two The Book of Lost Tales, Part One

The Book of Lost Tales, Part One The Book of Lost Tales 2

The Book of Lost Tales 2 Roverandom

Roverandom Smith of Wootton Major

Smith of Wootton Major The Fall of Arthur

The Fall of Arthur The Nature of Middle-earth

The Nature of Middle-earth The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring, The Two Towers, The Return of the King

The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring, The Two Towers, The Return of the King The Lay of Aotrou and Itroun

The Lay of Aotrou and Itroun lord_rings.qxd

lord_rings.qxd The Fall of Gondolin

The Fall of Gondolin The Book of Lost Tales, Part 1

The Book of Lost Tales, Part 1 The Book of Lost Tales, Part 2

The Book of Lost Tales, Part 2 The Lord of the Rings

The Lord of the Rings Tree and Leaf

Tree and Leaf The Children of Húrin

The Children of Húrin The Story of Kullervo

The Story of Kullervo Letters From Father Christmas

Letters From Father Christmas The History of Middle Earth: Volume 8 - The War of the Ring

The History of Middle Earth: Volume 8 - The War of the Ring Mr. Bliss

Mr. Bliss Unfinished Tales

Unfinished Tales The Adventures of Tom Bombadil

The Adventures of Tom Bombadil Beowulf: A Translation and Commentary, together with Sellic Spell

Beowulf: A Translation and Commentary, together with Sellic Spell The Silmarillion

The Silmarillion Beren and Lúthien

Beren and Lúthien