- Home

- J. R. R. Tolkien

The Adventures of Tom Bombadil Page 2

The Adventures of Tom Bombadil Read online

Page 2

Tolkien also decided that he was disappointed with Baynes’s cover art once he saw it in proof. A wraparound design, it features the mariner from Errantry on the upper cover and a sleeping Tom Bombadil on the lower, with a panoply of birds, fish, and other creatures against a backdrop of earth, sea, and sky. ‘Alas!’ Tolkien wrote to Ronald Eames, ‘it is only now … that I observe that as an illustration, especially one to fit the general title, the picture should have been reversed: with Bombadil on the front, and the Ship sailing left, westward!’ He was unhappy also with the publisher’s choice of lettering for the cover, a ‘heavy fat-serifed’ type, ‘at odds with the style of the picture’ (12 September 1962, A&U archive; Chronology, p. 597). But Allen & Unwin were working to a tight production schedule, and it was too late to effect any change.

The Adventures of Tom Bombadil and Other Verses from the Red Book was published on 22 November 1962. By then, Tolkien had received advance copies, and Rayner Unwin had noticed that the full-page art for Cat was awkwardly placed within the text of Fastitocalon and opposite an illustration for the latter – an accident of layout to allow two-colour printing for both pictures. Unwin and Tolkien agreed that, in any reprint, the order of Cat and Fastitocalon should be reversed and the art adjusted; this was done with the second Allen & Unwin printing in 1962 (and in the American edition from the first printing in 1963), and has been followed in all subsequent editions.

Tolkien wrote to Stanley Unwin, the chairman of George Allen & Unwin, on 28 November that he was ‘agreeably surprised’ at reviews of the Bombadil volume in the Times Literary Supplement and The Listener. ‘I expected remarks far more snooty and patronizing. Also I was rather pleased, since it seemed that the reviewers had both started out not wanting to be amused, but had failed to maintain their Victorian dignity intact’ (Letters, p. 322). The Times Literary Supplement review of 23 November 1962 (attributed to Alfred Duggan) called Tolkien ‘a wordsmith, an ingenious versifier, rather than a discoverer of new insights’, while Anthony Thwaite in The Listener (22 November) contrasted the ‘heavy-footed donnish waggery’ of Tolkien’s preface with the poems, which were ‘by turns gay, prattling, melancholy, nonsensical, mysterious. And what is most exciting and attractive about them is their superb technical skill. Professor Tolkien revealed in the verses scattered through The Hobbit that he had a talent for songs, riddling rhymes, and a kind of balladry. In The Adventures of Tom Bombadil the talent can be seen to be something close to genius.’ In response to the latter, Tolkien wondered to Stanley Unwin ‘why if a “professor” shows any knowledge of his professional techniques it must be “waggery”, but if a writer shows, say, knowledge of law or law-courts it is held interesting and creditable’ (28 November, Letters, p. 322). It seems likely that Tolkien also saw the review by Christopher Derrick in the Roman Catholic journal The Tablet (15 December 1962), which defended the Bombadil volume from charges of ‘whimsy’. With only a few exceptions, the book received positive reviews.

On 19 December, Tolkien was pleased to tell his son Michael that ‘“T.B.” sold nearly 8,000 copies before publication (caught on the hop they have had to reprint hastily), and that, even on a minute initial royalty, means more than is at all usual for anyone but [popular poet John] Betjeman to make on verse!’ (Letters, p. 322). On 23 December, he also wrote to Pauline Baynes that the collection was selling uncommonly well (for verse), and attributed its success in large part to her illustrations.

In 1952, Tolkien had recited The Man in the Moon Stayed Up Too Late, Oliphaunt, and The Stone Troll (the latter with variations) into a tape recorder owned by his friend George Sayer: these readings were issued first on a vinyl record in 1975, with other excerpts from The Lord of the Rings and The Hobbit. In 1967, he made a commercial recording of The Adventures of Tom Bombadil, The Hoard, The Man in the Moon Came Down Too Soon, The Mewlips, and Perry-the-Winkle for the album Poems and Songs of Middle Earth, which also featured Errantry performed by baritone William Elvin and composer Donald Swann, within Swann’s Tolkien song cycle The Road Goes Ever On. Tolkien also recorded at this session Errantry, Princess Mee, and The Sea-Bell, but these were issued only in 2001, with Tolkien’s other readings from 1967 and his recordings with George Sayer, as part of The J.R.R. Tolkien Audio Collection.

Although the preface and poems of The Adventures of Tom Bombadil and Other Verses from the Red Book have remained in print since 1962, they have not consistently appeared in a dedicated volume, rather than within a larger collection of shorter works. We are pleased to present them afresh, and to include for comparison earlier printed or manuscript versions (where earlier versions exist). It seems appropriate also to reprint another poem by Tolkien featuring Tom and Goldberry, Once upon a Time, first published three years after the Bombadil volume appeared, and a possible precursor, An Evening in Tavrobel.

Throughout this book, we follow the convention of referring to Tolkien’s larger mythology as ‘The Silmarillion’, in quotation marks, and the edition of its component tales published in 1977 as The Silmarillion, italicized. We have assumed, as Tolkien himself did in the preface to the Bombadil collection, that the reader has a certain degree of familiarity with (at least) The Lord of the Rings.

We are grateful to the Tolkien Estate for permission to reprint or newly publish writings by J.R.R. Tolkien; and for their assistance at many points in the making of this book, we are indebted to Christopher Tolkien, to Cathleen Blackburn of the solicitors Maier Blackburn, to the staff of the Bodleian Libraries, including Colin Harris, Catherine Parker, and Judith Priestman, and to the editors and production staff of HarperCollins, in particular David Brawn, Terence Caven, and Natasha Hughes. We also would like to thank Sr. Joan Breen and Sr. Barbara Jeffery of the Institute of Our Lady of Mercy, Bermondsey, for providing a copy of The Shadow Man from the Annual of Our Lady’s School, Abingdon, and Stephen Oliver of Our Lady’s School for facilitating this contact; and as always, Carl F. Hostetter and Arden R. Smith for helpful advice on Tolkien’s invented languages.

Christina Scull & Wayne G. Hammond

January 2014

PREFACE

The Red Book contains a large number of verses. A few are included in the narrative of the Downfall of the Lord of the Rings, or in the attached stories and chronicles; many more are found on loose leaves, while some are written carelessly in margins and blank spaces. Of the last sort most are nonsense, now often unintelligible even when legible, or half-remembered fragments. From these marginalia are drawn Nos. 4, 12, 13; though a better example of their general character would be the scribble, on the page recording Bilbo’s When winter first begins to bite:

The wind so whirled a weathercock

He could not hold his tail up;

The frost so nipped a throstlecock

He could not snap a snail up.

‘My case is hard! the throstle cried,

And ‘All is vane’ the cock replied;

And so they set their wail up.

The present selection is taken from the older pieces, mainly concerned with legends and jests of the Shire at the end of the Third Age, that appear to have been made by Hobbits, especially by Bilbo and his friends, or their immediate descendants. Their authorship is, however, seldom indicated. Those outside the narratives are in various hands, and were probably written down from oral tradition.

In the Red Book it is said that No. 5 was made by Bilbo, and No. 7 by Sam Gamgee. No. 8 is marked SG, and the ascription may be accepted. No. 11 is also marked SG, though at most Sam can only have touched up an older piece of the comic bestiary lore of which Hobbits appear to have been fond. In The Lord of the Rings Sam stated that No. 10 was traditional in the Shire.

No. 3 is an example of another kind which seems to have amused Hobbits: a rhyme or story which returns to its own beginning, and so may be recited until the hearers revolt. Several specimens are found in the Red Book, but the others are simple and crude. No. 3 is much the longest and most elaborate. It was evidently made by Bilbo. This is i

ndicated by its obvious relationship to the long poem recited by Bilbo, as his own composition, in the house of Elrond. In origin a ‘nonsense rhyme’, it is in the Rivendell version found transformed and applied, somewhat incongruously, to the High-elvish and Númenórean legends of Eärendil. Probably because Bilbo invented its metrical devices and was proud of them. They do not appear in other pieces in the Red Book. The older form, here given, must belong to the early days after Bilbo’s return from his journey. Though the influence of Elvish traditions is seen, they are not seriously treated, and the names used (Derrilyn, Thellamie, Belmarie, Aerie) are mere inventions in the Elvish style, and are not in fact Elvish at all.

The influence of the events at the end of the Third Age, and the widening of the horizons of the Shire by contact with Rivendell and Gondor, is to be seen in other pieces. No. 6, though here placed next to Bilbo’s Man-in-the-Moon rhyme, and the last item, No. 16, must be derived ultimately from Gondor. They are evidently based on the traditions of Men, living in shorelands and familiar with rivers running into the Sea. No. 6 actually mentions Belfalas (the windy bay of Bel), and the Sea-ward Tower, Tirith Aear, of Dol Amroth. No. 16 mentions the Seven Rivers1 that flowed into the Sea in the South Kingdom, and uses the Gondorian name, of High-elvish form, Fíriel, mortal woman.2 In the Langstrand and Dol Amroth there were many traditions of the ancient Elvish dwellings, and of the haven at the mouth of the Morthond from which ‘westward ships’ had sailed as far back as the fall of Eregion in the Second Age. These two pieces, therefore, are only re-handlings of Southern matter, though this may have reached Bilbo by way of Rivendell. No. 14 also depends on the lore of Rivendell, Elvish and Númenórean, concerning the heroic days at the end of the First Age; it seems to contain echoes of the Númenorean tale of Túrin and Mîm the Dwarf.

Nos. 1 and 2 evidently come from the Buckland. They show more knowledge of that country, and of the Dingle, the wooded valley of the Withywindle,3 than any Hobbits west of the Marish were likely to possess. They also show that the Bucklanders knew Bombadil,4 though, no doubt, they had as little understanding of his powers as the Shirefolk had of Gandalf’s: both were regarded as benevolent persons, mysterious maybe and unpredictable but nonetheless comic. No. 1 is the earlier piece, and is made up of various hobbit-versions of legends concerning Bombadil. No. 2 uses similar traditions, though Tom’s raillery is here turned in jest upon his friends, who treat it with amusement (tinged with fear); but it was probably composed much later and after the visit of Frodo and his companions to the house of Bombadil.

The verses, of hobbit origin, here presented have generally two features in common. They are fond of strange words, and of rhyming and metrical tricks – in their simplicity Hobbits evidently regarded such things as virtues or graces, though they were, no doubt, mere imitations of Elvish practices. They are also, at least on the surface, lighthearted or frivolous, though sometimes one may uneasily suspect that more is meant than meets the ear. No. 15, certainly of hobbit origin, is an exception. It is the latest piece and belongs to the Fourth Age; but it is included here, because a hand has scrawled at its head Frodos Dreme. That is remarkable, and though the piece is most unlikely to have been written by Frodo himself, the title shows that it was associated with the dark and despairing dreams which visited him in March and October during his last three years. But there were certainly other traditions, concerning Hobbits that were taken by the ‘wandering-madness’, and if they ever returned, were afterwards queer and uncommunicable. The thought of the Sea was ever-present in the background of hobbit imagination; but fear of it and distrust of all Elvish lore, was the prevailing mood in the Shire at the end of the Third Age, and that mood was certainly not entirely dispelled by the events and changes with which that Age ended.

Old Tom Bombadil was a merry fellow;

bright blue his jacket was and his boots were yellow,

green were his girdle and his breeches all of leather;

he wore in his tall hat a swan-wing feather.

He lived up under Hill, where the Withywindle

ran from a grassy well down into the dingle.

Old Tom in summertime walked about the meadows

gathering the buttercups, running after shadows,

tickling the bumblebees that buzzed among the flowers,

sitting by the waterside for hours upon hours.

There his beard dangled long down into the water:

up came Goldberry, the River-woman’s daughter;

pulled Tom’s hanging hair. In he went a-wallowing

under the water-lilies, bubbling and a-swallowing.

‘Hey, Tom Bombadil! Whither are you going?’

said fair Goldberry. ‘Bubbles you are blowing,

frightening the finny fish and the brown water-rat,

startling the dabchicks, and drowning your feather-hat!’

‘You bring it back again, there’s a pretty maiden!’

said Tom Bombadil. ‘I do not care for wading.

Go down! Sleep again where the pools are shady

far below willow-roots, little water-lady!’

Back to her mother’s house in the deepest hollow

swam young Goldberry. But Tom, he would not follow;

on knotted willow-roots he sat in sunny weather,

drying his yellow boots and his draggled feather.

Up woke Willow-man, began upon his singing,

sang Tom fast asleep under branches swinging;

in a crack caught him tight: snick! it closed together,

trapped Tom Bombadil, coat and hat and feather.

‘Ha, Tom Bombadil! What be you a-thinking,

peeping inside my tree, watching me a-drinking

deep in my wooden house, tickling me with feather,

dripping wet down my face like a rainy weather?’

‘You let me out again, Old Man Willow!

I am stiff lying here; they’re no sort of pillow,

your hard crooked roots. Drink your river-water!

Go back to sleep again like the River-daughter!’

Willow-man let him loose when he heard him speaking;

locked fast his wooden house, muttering and creaking,

whispering inside the tree. Out from willow-dingle

Tom went walking on up the Withywindle.

Under the forest-eaves he sat a while a-listening:

on the boughs piping birds were chirruping and whistling.

Butterflies about his head went quivering and winking,

until grey clouds came up, as the sun was sinking.

Then Tom hurried on. Rain began to shiver,

round rings spattering in the running river;

a wind blew, shaken leaves chilly drops were dripping;

into a sheltering hole Old Tom went skipping.

Out came Badger-brock with his snowy forehead

and his dark blinking eyes. In the hill he quarried

with his wife and many sons. By the coat they caught him,

pulled him inside their earth, down their tunnels brought him.

Inside their secret house, there they sat a-mumbling:

‘Ho, Tom Bombadil! Where have you come tumbling,

bursting in the front-door? Badger-folk have caught you.

You’ll never find it out, the way that we have brought you!’

‘Now, old Badger-brock, do you hear me talking?

You show me out at once! I must be a-walking.

Show me to your backdoor under briar-roses;

then clean grimy paws, wipe your earthy noses!

Go back to sleep again on your straw pillow,

like fair Goldberry and Old Man Willow!’

Then all the Badger-folk said: ‘We beg your pardon!’

They showed Tom out again to their thorny garden,

went back and hid themselves, a-shivering and a-shaking,

blocked up all their doors, earth together raking.

Rain had passed. The sky was clear, and in the

summer-gloaming

Old Tom Bombadil laughed as he came homing,

unlocked his door again, and opened up a shutter.

In the kitchen round the lamp moths began to flutter;

Tom through the window saw waking stars come winking,

and the new slender moon early westward sinking.

Dark came under Hill. Tom, he lit a candle;

upstairs creaking went, turned the door-handle.

‘Hoo, Tom Bombadil! Look what night has brought you!

I’m here behind the door. Now at last I’ve caught you!

You’d forgotten Barrow-wight dwelling in the old mound

up there on hill-top with the ring of stones round.

He’s got loose again. Under earth he’ll take you.

Poor Tom Bombadil, pale and cold he’ll make you!’

‘Go out! Shut the door, and never come back after!

Take away gleaming eyes, take your hollow laughter!

Go back to grassy mound, on your stony pillow

lay down your bony head, like Old Man Willow,

like young Goldberry, and Badger-folk in burrow!

The Fellowship of the Ring

The Fellowship of the Ring The Hobbit

The Hobbit The Two Towers

The Two Towers The Return of the King

The Return of the King Tales From the Perilous Realm

Tales From the Perilous Realm Leaf by Niggle

Leaf by Niggle The Silmarillon

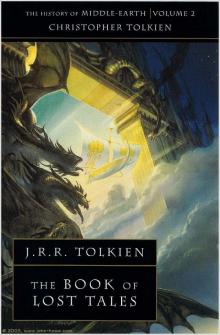

The Silmarillon The Book of Lost Tales, Part Two

The Book of Lost Tales, Part Two The Book of Lost Tales, Part One

The Book of Lost Tales, Part One The Book of Lost Tales 2

The Book of Lost Tales 2 Roverandom

Roverandom Smith of Wootton Major

Smith of Wootton Major The Fall of Arthur

The Fall of Arthur The Nature of Middle-earth

The Nature of Middle-earth The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring, The Two Towers, The Return of the King

The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring, The Two Towers, The Return of the King The Lay of Aotrou and Itroun

The Lay of Aotrou and Itroun lord_rings.qxd

lord_rings.qxd The Fall of Gondolin

The Fall of Gondolin The Book of Lost Tales, Part 1

The Book of Lost Tales, Part 1 The Book of Lost Tales, Part 2

The Book of Lost Tales, Part 2 The Lord of the Rings

The Lord of the Rings Tree and Leaf

Tree and Leaf The Children of Húrin

The Children of Húrin The Story of Kullervo

The Story of Kullervo Letters From Father Christmas

Letters From Father Christmas The History of Middle Earth: Volume 8 - The War of the Ring

The History of Middle Earth: Volume 8 - The War of the Ring Mr. Bliss

Mr. Bliss Unfinished Tales

Unfinished Tales The Adventures of Tom Bombadil

The Adventures of Tom Bombadil Beowulf: A Translation and Commentary, together with Sellic Spell

Beowulf: A Translation and Commentary, together with Sellic Spell The Silmarillion

The Silmarillion Beren and Lúthien

Beren and Lúthien