- Home

- J. R. R. Tolkien

The Adventures of Tom Bombadil Page 3

The Adventures of Tom Bombadil Read online

Page 3

Go back to buried gold and forgotten sorrow!’

Out fled Barrow-wight through the window leaping,

through the yard, over wall like a shadow sweeping,

up hill wailing went back to leaning stone-rings,

back under lonely mound, rattling his bone-rings.

Old Tom Bombadil lay upon his pillow

sweeter than Goldberry, quieter than the Willow,

snugger than the Badger-folk or the Barrow-dwellers;

slept like a humming-top, snored like a bellows.

He woke in morning-light, whistled like a starling,

sang, ‘Come, derry-dol, merry-dol, my darling!’

He clapped on his battered hat, boots, and coat and feather;

opened the window wide to the sunny weather.

Wise old Bombadil, he was a wary fellow;

bright blue his jacket was, and his boots were yellow.

None ever caught old Tom in upland or in dingle,

walking the forest-paths, or by the Withywindle,

or out on the lily-pools in boat upon the water.

But one day Tom, he went and caught the River-daughter,

in green gown, flowing hair, sitting in the rushes,

singing old water-songs to birds upon the bushes.

He caught her, held her fast! Water-rats went scuttering

reeds hissed, herons cried, and her heart was fluttering.

Said Tom Bombadil: ‘Here’s my pretty maiden!

You shall come home with me! The table is all laden:

yellow cream, honeycomb, white bread and butter;

roses at the window-sill and peeping round the shutter.

You shall come under Hill! Never mind your mother

in her deep weedy pool: there you’ll find no lover!’

Old Tom Bombadil had a merry wedding,

crowned all with buttercups, hat and feather shedding;

his bride with forgetmenots and flag-lilies for garland

was robed all in silver-green. He sang like a starling,

hummed like a honey-bee, lilted to the fiddle,

clasping his river-maid round her slender middle.

Lamps gleamed within his house, and white was the bedding;

in the bright honey-moon Badger-folk came treading,

danced down under Hill, and Old Man Willow

tapped, tapped at window-pane, as they slept on the pillow,

on the bank in the reeds River-woman sighing

heard old Barrow-wight in his mound crying.

Old Tom Bombadil heeded not the voices,

taps, knocks, dancing feet, all the nightly noises;

slept till the sun arose, then sang like a starling:

‘Hey! Come derry-dol, merry-dol, my darling!’

sitting on the door-step chopping sticks of willow,

while fair Goldberry combed her tresses yellow.

The old year was turning brown; the West Wind was calling;

Tom caught a beechen leaf in the Forest falling.

‘I’ve caught a happy day blown me by the breezes!

Why wait till morrow-year? I’ll take it when me pleases.

This day I’ll mend my boat and journey as it chances

west down the withy-stream, following my fancies!’

Little Bird sat on twig. ‘Whillo, Tom! I heed you.

I’ve a guess, I’ve a guess where your fancies lead you.

Shall I go, shall I go, bring him word to meet you?’

‘No names, you tell-tale, or I’ll skin and eat you,

babbling in every ear things that don’t concern you!

If you tell Willow-man where I’ve gone, I’ll burn you,

roast you on a willow-spit. That’ll end your prying!’

Willow-wren cocked her tail, piped as she went flying:

‘Catch me first, catch me first! No names are needed.

I’ll perch on his hither ear: the message will be heeded.

“Down by Mithe,” I’ll say, “just as sun is sinking.”

Hurry up, hurry up! That’s the time for drinking!’

Tom laughed to himself: ‘Maybe then I’ll go there.

I might go by other ways, but today I’ll row there.’

He shaved oars, patched his boat; from hidden creek he hauled her

through reed and sallow-brake, under leaning alder,

then down the river went, singing: ‘Silly-sallow,

Flow withy-willow-stream over deep and shallow!’

‘Whee! Tom Bombadil! Whither be you going,

bobbing in a cockle-boat, down the river rowing?’

‘Maybe to Brandywine along the Withywindle;

maybe friends of mind fire for me will kindle

down by the Hays-end. Little folk I know there,

kind at the day’s end. Now and then I go there.’

‘Take word to my kin, bring me back their tidings!

Tell me of diving pools and the fishes’ hidings!’

‘Nay then,’ said Bombadil, ‘I am only rowing

just to smell the water like, not on errands going.’

‘Tee hee! Cocky Tom! Mind your tub don’t founder!

Look out for willow-snags! I’d laugh to see you flounder.’

‘Talk less, Fisher Blue! Keep your kindly wishes!

Fly off and preen yourself with the bones of fishes!

Gay lord on your bough, at home a dirty varlet

living in a sloven house, though your breast be scarlet.

I’ve heard of fisher-birds beak in air a-dangling

to show how the wind is set: that’s an end of angling!’

The King’s fisher shut his beak, winked his eye, as singing

Tom passed under bough. Flash! then he went winging;

dropped down jewel-blue a feather, and Tom caught it

gleaming in a sun-ray: a pretty gift he thought it.

He stuck it in his tall hat, the old feather casting:

‘Blue now for Tom,’ he said, ‘a merry hue and lasting!’

Rings swirled round his boat, he saw the bubbles quiver.

Tom slapped his oar, smack! at a shadow in the river.

‘Hoosh! Tom Bombadil! ’Tis long since last I met you.

Turned water-boatman, eh? What if I upset you?’

‘What? Why, Whisker-lad, I’d ride you down the river.

My fingers on your back would set your hide a-shiver.’

‘Pish, Tom Bombadil! I’ll go and tell my mother;

“Call all our kin to come, father, sister, brother!

Tom’s gone mad as a coot with wooden legs: he’s paddling

down Withywindle stream, an old tub a-straddling!”’

‘I’ll give your otter-fell to Barrow-wights. They’ll taw you!

Then smother you in gold-rings! Your mother if she saw you,

she’d never know her son, unless ’twas by a whisker.

Nay, don’t tease old Tom, until you be far brisker!’

‘Whoosh!’ said otter-lad, river-water spraying

over Tom’s hat and all; set the boat a-swaying,

dived down under it, and by the bank lay peering,

till Tom’s merry song faded out of hearing.

Old Swan of Elvet-isle sailed past him proudly,

gave Tom a black look, snorted at him loudly.

Tom laughed: ‘You old cob, do you miss your feather?

Give me a new one then! The old was worn by weather.

Could you speak a fair word, I would love you dearer:

long neck and dumb throat, but still a haughty sneerer!

If one day the King returns, in upping he may take you,

brand your yellow bill, and less lordly make you!’

Old Swan huffed his wings, hissed, and paddled faster;

in his wake bobbing on Tom went rowing after.

Tom came to Withy-weir. Down the river rushing

foamed into Windle-reach, a-bubbling and a-splashing;<

br />

bore Tom over stone spinning like a windfall,

bobbing like a bottle-cork, to the hythe at Grindwall.

‘Hoy! Here’s Woodman Tom with his billy-beard on!’

laughed all the little folk of Hays-end and Breredon.

‘Ware, Tom! We’ll shoot you dead with our bows and arrows!

We don’t let Forest-folk nor bogies from the Barrows

cross over Brandywine by cockle-boat nor ferry.’

‘Fie, little fatbellies! Don’t ye make so merry!

I’ve seen hobbit-folk digging holes to hide ’em,

frightened if a horny goat or a badger eyed ’em,

afeared of the moony-beams, their old shadows shunning.

I’ll call the orks on you: that’ll send you running!’

‘You may call, Woodman Tom. And you can talk your beard off.

Three arrows in your hat! You we’re not afeared of!

Where would you go to now? If for beer you’re making,

the barrels aint deep enough in Breredon for your slaking!’

‘Away over Brandywine by Shirebourn I’d be going,

but too swift for cockle-boat the river now is flowing.

I’d bless little folk that took me in their wherry,

wish them evenings fair and many mornings merry.’

Red flowed the Brandywine; with flame the river kindled,

as sun sank beyond the Shire, and then to grey it dwindled.

Mithe Steps empty stood. None was there to greet him.

Silent the Causeway lay. Said Tom: ‘A merry meeting!’

Tom stumped along the road, as the light was failing.

Rushey lamps gleamed ahead. He heard a voice him hailing.

‘Whoa there!’ Ponies stopped, wheels halted sliding.

Tom went plodding past, never looked beside him.

‘Ho there! beggarman tramping in the Marish!

What’s your business here? Hat all stuck with arrows!

Someone’s warned you off, caught you at your sneaking?

Come here! Tell me now what it is you’re seeking!

Shire-ale, I’ll be bound, though you’ve not a penny.

I’ll bid them lock their doors, and then you won’t get any!’

‘Well, well, Muddy-feet! From one that’s late for meeting

away back by the Mithe that’s a surly greeting!

You old farmer fat that cannot walk for wheezing,

cart-drawn like a sack, ought to be more pleasing.

Penny-wise tub-on-legs! A beggar can’t be chooser,

or else I’d bid you go, and you would be the loser.

Come, Maggot! Help me up! A tankard now you owe me.

Even in cockshut light an old friend should know me!’

Laughing they drove away, in Rushey never halting,

though the inn open stood and they could smell the malting.

They turned down Maggot’s Lane, rattling and bumping,

Tom in the farmer’s cart dancing round and jumping.

Stars shone on Bamfurlong, and Maggot’s house was lighted;

fire in the kitchen burned to welcome the benighted.

Maggot’s sons bowed at door, his daughters did their curtsy,

his wife brought tankards out for those that might be thirsty.

Songs they had and merry tales, the supping and the dancing;

Goodman Maggot there for all his belt was prancing,

Tom did a hornpipe when he was not quaffing,

daughters did the Springle-ring, goodwife did the laughing.

When others went to bed in hay, fern, or feather,

close in the inglenook they laid their heads together,

old Tom and Muddy-feet, swapping all the tidings

from Barrow-downs to Tower Hills: of walkings and of ridings;

of wheat-ear and barley-corn, of sowing and of reaping;

queer tales from Bree, and talk at smithy, mill, and cheaping;

rumours in whispering trees, south-wind in the larches,

tall Watchers by the Ford, Shadows on the marches.

Old Maggot slept at last in chair beside the embers.

Ere dawn Tom was gone: as dreams one half remembers,

some merry, some sad, and some of hidden warning.

None heard the door unlocked; a shower of rain at morning

his footprints washed away, at Mithe he left no traces,

at Hays-end they heard no song nor sound of heavy paces.

Three days his boat lay by the hythe at Grindwall,

and then one morn was gone back up Withywindle.

Otter-folk, hobbits said, came by night and loosed her,

dragged her over weir, and up stream they pushed her.

Out from Elvet-isle Old Swan came sailing,

in beak took her painter up in the water trailing,

drew her proudly on; otters swam beside her

round old Willow-man’s crooked roots to guide her;

the King’s fisher perched on bow, on thwart the wren was singing,

merrily the cockle-boat homeward they were bringing.

To Tom’s creek they came at last. Otter-lad said: ‘Whish now!

What’s a coot without his legs, or a finless fish now?’

O! silly-sallow-willow-stream! The oars they’d left behind them!

Long they lay at Grindwall hythe for Tom to come and find them.

There was a merry passenger,

a messenger, a mariner:

he built a gilded gondola

to wander in, and had in her

a load of yellow oranges

and porridge for his provender;

he perfumed her with marjoram

and cardamon and lavender.

He called the winds of argosies

with cargoes in to carry him

across the rivers seventeen

that lay between to tarry him.

He landed all in loneliness

where stonily the pebbles on

the running river Derrilyn

goes merrily for ever on.

He journeyed then through meadow-lands

to Shadow-land that dreary lay,

and under hill and over hill

went roving still a weary way.

He sat and sang a melody,

his errantry a-tarrying;

he begged a pretty butterfly

that fluttered by to marry him.

She scorned him and she scoffed at him,

she laughed at him unpitying;

so long he studied wizardry

and sigaldry and smithying.

He wove a tissue airy-thin

to snare her in; to follow her

he made him beetle-leather wing

and feather wing of swallow-hair.

He caught her in bewilderment

with filament of spider-thread;

he made her soft pavilions

of lilies, and a bridal bed

of flowers and of thistle-down

to nestle down and rest her in;

and silken webs of filmy white

and silver light he dressed her in.

He threaded gems in necklaces,

but recklessly she squandered them

and fell to bitter quarrelling;

then sorrowing he wandered on,

and there he left her withering,

as shivering he fled away;

with windy weather following

on swallow-wing he sped away.

He passed the archipelagoes

where yellow grows the marigold,

where countless silver fountains are,

and mountains are of fairy-gold.

He took to war and foraying,

a-harrying beyond the sea,

and roaming over Belmarie

and Thellamie and Fantasie.

He made a shield and morion

of coral and of ivory,

a sword he made of emerald,

and terrible his rivalry

with elven-knights of Aerie

and Faerie, with paladins

that golden-haired and shining-eyed

came riding by and challenged him.

Of crystal was his habergeon,

his scabbard of chalcedony;

with silver tipped at plenilune

his spear was hewn of ebony.

His javelins were of malachite

and stalactite — he brandished them,

and went and fought the dragon-flies

of Paradise, and vanquished them.

He battled with the Dumbledors,

the Hummerhorns, and Honeybees,

and won the Golden Honeycomb;

and running home on sunny seas

in ship of leaves and gossamer

with blossom for a canopy,

he sat and sang, and furbished up

and burnished up his panoply.

He tarried for a little while

in little isles that lonely lay,

and found there naught but blowing grass;

and so at last the only way

he took, and turned, and coming home

with honeycomb, to memory

his message came, and errand too!

In derring-do and glamoury

he had forgot them, journeying

and tourneying, a wanderer.

So now he must depart again

and start again his gondola,

for ever still a messenger,

a passenger, a tarrier,

a-roving as a feather does,

a weather-driven mariner.

Little Princess Mee

Lovely was she

As in elven-song is told:

She had pearls in hair

All threaded fair;

Of gossamer shot with gold

Was her kerchief made,

And a silver braid

Of stars about her throat.

Of moth-web light

All moonlit-white

She wore a woven coat,

And round her kirtle

Was bound a girdle

Sewn with diamond dew.

She walked by day

Under mantle grey

And hood of clouded blue;

But she went by night

All glittering bright

Under the starlit sky,

And her slippers frail

Of fishes’ mail

Flashed as she went by

To her dancing-pool,

And on mirror cool

Of windless water played.

As a mist of light

In whirling flight

A glint like glass she made

Wherever her feet

Of silver fleet

The Fellowship of the Ring

The Fellowship of the Ring The Hobbit

The Hobbit The Two Towers

The Two Towers The Return of the King

The Return of the King Tales From the Perilous Realm

Tales From the Perilous Realm Leaf by Niggle

Leaf by Niggle The Silmarillon

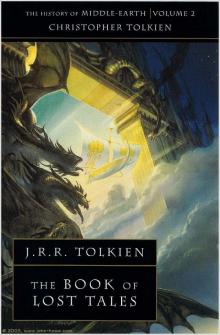

The Silmarillon The Book of Lost Tales, Part Two

The Book of Lost Tales, Part Two The Book of Lost Tales, Part One

The Book of Lost Tales, Part One The Book of Lost Tales 2

The Book of Lost Tales 2 Roverandom

Roverandom Smith of Wootton Major

Smith of Wootton Major The Fall of Arthur

The Fall of Arthur The Nature of Middle-earth

The Nature of Middle-earth The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring, The Two Towers, The Return of the King

The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring, The Two Towers, The Return of the King The Lay of Aotrou and Itroun

The Lay of Aotrou and Itroun lord_rings.qxd

lord_rings.qxd The Fall of Gondolin

The Fall of Gondolin The Book of Lost Tales, Part 1

The Book of Lost Tales, Part 1 The Book of Lost Tales, Part 2

The Book of Lost Tales, Part 2 The Lord of the Rings

The Lord of the Rings Tree and Leaf

Tree and Leaf The Children of Húrin

The Children of Húrin The Story of Kullervo

The Story of Kullervo Letters From Father Christmas

Letters From Father Christmas The History of Middle Earth: Volume 8 - The War of the Ring

The History of Middle Earth: Volume 8 - The War of the Ring Mr. Bliss

Mr. Bliss Unfinished Tales

Unfinished Tales The Adventures of Tom Bombadil

The Adventures of Tom Bombadil Beowulf: A Translation and Commentary, together with Sellic Spell

Beowulf: A Translation and Commentary, together with Sellic Spell The Silmarillion

The Silmarillion Beren and Lúthien

Beren and Lúthien